Abstract

We present an investigation into the long-run effects of financialisation on income distribution before the financial and economic crises for Germany, one of the major mercantilist export-led economies. The analysis builds on a Kaleckian approach towards the examination of the effects of financialisation on income distribution, as suggested by Hein (Camb J Econ. doi:10.1093/cje/bet038, 2014a). First, we show that Germany saw considerable re-distribution of income starting in the early 1980s, which accelerated in the early 2000s, in particular. Examining the three main channels through which financialisation (and neo-liberalism) are supposed to have affected the wage or the labour income share, according to the Kaleckian approach, we provide evidence for the existence of each of these channels in Germany since the mid-1990s, when several institutional changes provided the conditions for an increasing dominance of finance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is by now widely agreed among both heterodox and some orthodox authors that the financial and economic crises, which started in 2007, were caused by changes in income distribution over the previous decades and the emerging current account imbalances at the global and at regional (Euro area) levels, apart from malfunctioning deregulated financial markets.Footnote 1 These developments have been determined by policies aimed at deregulation and liberalisation of labour, goods and financial markets, both at the national and the international level, and the reduction of government intervention into the market economy and of government demand management. This broad policy stance may be called ‘neo-liberalism’, describing the policies implemented—to different degrees in different capitalist economies—since the late 1970s/early 1980s or later. ‘Financialisation’ or ‘finance-dominated capitalism’—we use these terms interchangeably—is interrelated and overlaps with neo-liberalism.Footnote 2 Epstein (2005a, p. 3) has presented a vague but widely accepted definition, arguing that ‘\([{\ldots }]\) financialization means the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies’.

The features of financialisation or finance-dominated capitalism are wide ranging and have been described and analysed extensively and in detail by many authors. Detailed empirical case studies have been presented by, for example, the contributions in Epstein (2005b), and by Krippner (2005), Orhangazi (2008a, b), and (Palley (2008, 2013), Chapter 2) for the US, by Stockhammer (2008) for Europe, by Van Treeck (2009) and Van Treeck et al. (2007) for Germany as compared to the US, and recently and more extensively by Detzer et al. (2013) for Germany.Footnote 3

From a macroeconomic perspective, Hein (2012) has claimed that finance-dominated capitalism can be characterised more precisely by the following elements.

-

1.

With regard to distribution, the dominance of finance has been conducive to a rising gross profit share, including retained profits, dividends and interest payments, and thus a falling labour income share, on the one hand, and to increasing inequality of wages and rising top management salaries, on the other hand. The major reasons for this have been falling bargaining power of trade unions, rising profit claims imposed, in particular, by increasingly powerful rentiers, and a change in the sectoral composition of the economy in favour of the financial corporate sector.

-

2.

Regarding investment in the capital stock, financialisation has been characterised by increasing shareholder power vis-à-vis management and workers, an increasing rate of return on equity and bonds held by rentiers, and an alignment of management with shareholder interests through short-run performance-related pay schemes such as bonuses and stock option programmes. On the one hand, this has imposed short-termism on management and has served to decrease managements’ animal spirits with respect to real investment in the capital stock and the long-run growth of the firm and to increase the preference for financial investment, which generates high profits in the short run. On the other hand, it has drained internal means of finance for real investment purposes from corporations, through increasing dividend payments and share buybacks, in order to boost stock prices and thus shareholder value. These ‘preference’ and ‘internal means of finance’ channels have each had partially negative effects on firms’ real investment in the capital stock, and hence also on the long-run growth potential of the economy to the extent that productivity growth is capital embodied.

-

3.

Regarding consumption, the dominance of finance has generated increasing potential for wealth-based and debt-financed consumption expenditures, thus creating the potential to compensate for the demand-depressing effects of financialisation, which were imposed on the economy via redistribution and the impact on real investment. Stock market and housing price booms have each increased notional wealth against which households were willing to borrow. Changing norms (conspicuous consumption, ‘keeping up with the Joneses’), new financial instruments (credit card debt, home equity lending), and deterioration of creditworthiness standards, triggered by debt securitisation and ‘originate and distribute’ strategies of banks, made credit increasingly available to low income, low wealth households, in particular. This allowed for consumption to rise faster than the median income in several countries and thus to stabilise aggregate demand. But it also generated increasing debt-income ratios of private households and thus increasing financial fragility.

-

4.

The deregulation and liberalisation of international capital markets and capital accounts have created the potential to run and finance persistent current account deficits. Some countries could therefore rely on debt-led soaring private consumption demand as the main driver of aggregate demand and GDP growth, generating and accepting concomitant rising deficits in their trade and current account balances. Other countries focussed on mercantilist export-led strategies as an alternative to generating demand in the face of redistribution at the expense of (low) labour incomes, stagnating consumption demand and weak real investment, and have hence accumulated increasing surpluses in their trade and current account balances. However, this constellation generated the problems of increasing foreign indebtedness and international financial fragility.

In this paper we will focus on the first and most basic element of financialisation viewed from a macroeconomic perspective: We will provide a deeper investigation of the long-run effects of financialisation on income distribution in one of the major mercantilist export-led countries, namely Germany, before the crisis. The focus will be on the period of finance-dominated capitalism, which is supposed to have started in the early 1980s in the US and other countries, but considerably later in Germany. As analysed in more detail in Detzer et al. (2013) and Detzer (2014), the most important changes in the German financial sector which contributed to an increasing dominance of finance took place in the course of the 1990s: in 1991 the abolition of the stock exchange tax, in 1998 the legalisation of share buybacks, in 2002 the abolition of capital gains taxes for corporations, and in 2004 the legalisation of hedge funds, among others. At the same time, many of the big banks shifted their activities from traditional commercial banking towards investment banking and the German company network was increasingly dissolved. With those changes, a much more active market for corporate control emerged, along with the establishment of new financial actors, such as hedge funds and private equity funds. We would thus expect to see some effects of financialisation on income distribution starting in the early/mid 1990s.

The paper builds on the more general examination of the effects of financialisation on income distribution in Hein (2014a) who provides a Kaleckian theoretical framework and a literature review on the general empirical and econometric evidence related to the channels through which financialisation should have affected functional income distribution, in particular, according to this theoretical approach. In Sect. 2 we will start with an empirical overview of different dimensions of (re-)distribution in Germany: functional distribution, personal/household distribution and finally the share and composition of top incomes. Having reviewed the empirical developments of several indicators of income distribution, we will then focus on functional distribution, because, according to Atkinson (2009), the development of functional income distribution is important for the other dimensions of distribution, as well as for the macroeconomic effects of distributional changes. In Sect. 3 we will briefly reiterate the Kaleckian analysis of the main channels of influence of neo-liberalism and finance-dominated capitalism on the tendency of the labour income share to fall, as suggested by Hein (2014a). And in Sect. 4 we will then review the empirical evidence for these channels for the case of Germany, in particular. Section 5 will summarise and conclude. The scope of this paper is thus limited to providing a Kaleckian view on the long-run effects of financialisation on income distribution in Germany before the crisis. It will neither deal with any further effects of financialisation and re-distribution on consumption, investment and the German macroeconomy as a whole, nor will the financial and economic crises and the recovery in Germany be discussed. For these issues, the interested reader is referred to Detzer et al. (2013) and Detzer and Hein (2014), for example.

Trends of Re-distribution in Germany

The period of finance-dominated capitalism has been associated with a massive redistribution of income. First, functional income distribution has changed at the expense of labour and in favour of broad capital income in several countries (Table 1). The labour income share, as a measure taken from the national accounts and corrected for the changes in the composition of employment regarding employees and self-employed, shows a falling trend in the developed capitalist economies considered here, from the early 1980s until the Great Recession, if we look at cyclical averages in order to eliminate cyclical fluctuations due to the well-known counter-cyclical properties of the labour income share. As can be seen, the fall in Germany was considerable, in particular from the cycle of the 1990s to the cycle of the early 2000s. However, redistribution was even more pronounced in several other countries, as for example Austria, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Japan.

Second, personal income distribution has become more unequal in most of the countries from the mid-1980s until the mid-2000s. Taking the Gini coefficient as an indicator, this is true for the distribution of market income, with the Netherlands being the only exception in the data set (Table 2). Germany is amongst those countries showing a considerable increase in inequality, which was only exceeded in Finland, Italy, Portugal the UK and Japan. If re-distribution via taxes and social policies by the state is included and the distribution of disposable income is considered, Belgium, France, Greece, Ireland, and Spain have not seen an increase in their Gini coefficients. In Germany, redistribution via taxes and social transfers has been considerable and not been decreasing over time. However, this did not prevent the Gini coefficient for disposable income from increasing. On the contrary, together with Finland, Italy, Portugal, Sweden and the US the increase in Germany was most pronounced. In fact, according to the OECD (2008) applying further indicators for inequality, Germany is one of the countries where the dispersion of disposable income increased the most in the early 2000s before the Great Recession. And as can be seen in Table 3, this redistribution was mainly at the expense of those with very low incomes. While the P90/P10 ratio for disposable income increased significantly, the P90/P50 ratio hardly increased. The P50/P10 ratio also slightly increased.Footnote 4

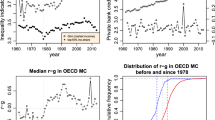

Third, as data based on tax reports provided by Alvaredo et al. (2014) have shown, there has been an explosion of the shares of the very top incomes since the early 1980s in the US and the UK, which, prior to the financial crisis and the Great Recession, have again reached levels of the mid-1920s in the US and the mid-1930s in the UK. Although Germany has not yet seen such an increase for the top 1 %, top 0.1 % or top 0.01 % income shares (Fig. 1), it should be noted that the share of the top 0.1 %, for example, has been substantially higher in this country than in the US or the UK for longer periods of time and that it was only surpassed by the US and the UK in the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, respectively (Hein 2014a). Furthermore, if we take a look at the top 10 % income share, including capital gains, a rising trend from the early 1980s until 2007 can be observed, when it reached the level of the early 1930s, excluding capital gains for the earlier time period.

Top income shares in Germany, 1891–2007 (in per cent of national income). Source: Alvaredo et al. (2014), our presentation

Taking a look at the composition of top incomes, the increase in the income share of the top 0.1 % in the US has mainly been driven by an increase in top salaries (wages and salaries, bonuses, exercised stock-options and pensions) since the 1970s, and, since the mid 1980s, also in entrepreneurial income (Alvaredo et al. 2014; Hein 2014a). Remuneration of top management (‘working rich’) has therefore contributed significantly, but not exclusively, to rising inequality in the US in the period of finance-dominated capitalism. Whereas top management salaries have contributed up to more than 50 % to the income of the top 0.1 % income share in the US, in Germany top management salaries have so far played a minor role. However, their share increased from 15 % in 1992 to 22.4 % in 2003 (Bach et al. 2009). Anselmann and Krämer (2012) also point out that in Germany the rise in top income shares was driven largely by an increase in salaries, rather than capital income. This development can be explained by the increasing compensation for top managers and financial professionals, which resulted in the phenomenon of the ‘working rich’. Similar results were also found by Dünhaupt (2011) when decomposing the gross market income of the top 1 % of the income share for Germany (Fig. 2). Although the data provided does not extend beyond 2003, one can see the increase in the relative importance of top management salaries compared with capital income and business income. The trend towards higher top management salaries is confirmed by Detzer (2014), considering salaries of management boards in the 30 top-listed German companies (DAX30). Those salaries increased only moderately from 1987 until 1995, with an average of 5 % per year. From then until 2007, however, they increased strongly, averaging 15 % per year.

Top 1 % income share in gross market income and its composition in Germany, 1992, 1998 and 2003 (in per cent of national income). Business income refers to the taxable income from agriculture, forestry, unincorporated business enterprise, and self-employed activities, including professional services. Capital income includes all capital income from private investments, except income from business activity. Source: (Dünhaupt (2011), p. 27)

The Effect of Financialisation on Income Distribution: A Kaleckian Approach

To what extent can these tendencies towards redistribution in Germany be related to the increasing dominance of finance? Hein (2014a) has reviewed the recent general empirical literature on the determinants of income shares against the background of the Kaleckian theory of distribution, in order to identify the channels through which financialisation and neo-liberalism have affected functional income distribution (Table 4). According to the Kaleckian approach (Kalecki 1954, Part I; Hein 2014b, Chapter 5), the gross profit share in national income, which includes retained earnings, dividend, interest and rent payments, as well as overhead costs (thus also top management salaries) has three major determinants.

First, the profit share is affected by firms’ pricing in incompletely competitive goods markets, i.e. by the mark-up on unit variable costs. The mark-up itself is determined by: (a) the degree of industrial concentration and by the relevance of price competition relative to other instruments of competition (marketing, product differentiation) in the respective industries or sectors, i.e. by the degree of price competition in the goods market; (b) the bargaining power of trade unions, because in a heterogeneous environment with differences in unit wage cost growth between firms, industries or sectors, the firm’s or the industry’s ability to shift changes in nominal unit wage costs to prices is constrained by competition of other firms or industries which do not have to face the same increase in unit wage costs; and (c) overhead costs and gross profit targets, because the mark-up has to cover overhead costs and distributed profits.

Second, with mark-up pricing on unit variable costs, i.e. material plus wage costs, the profit share in national income is affected by unit (imported) material costs relative to unit wage costs. With a constant mark-up, an increase in unit material costs will thus increase the profit share in national income.

And third, the aggregate profit share of the economy as a whole is a weighted average of the industry or sector profit shares. Since profit shares differ among industries and sectors, the aggregate profit share is therefore affected by the industry or sector composition of the economy.

Integrating some stylized facts of financialisation and neo-liberalism into this approach and reviewing the respective international empirical and econometric literature, Hein (2014a) has argued that there is some convincing empirical evidence that financialisation and neo-liberalism have contributed to the rising gross profit share, and hence to the falling labour income share since the early 1980s, through three main channels.Footnote 5

First, the shift in the sector composition of the economy, from the public sector and the non-financial business sector with higher labour income shares towards the financial business sector with a lower labour income share, has contributed to the fall in the labour income share for the economy as a whole in some countries.

Second, the increase in management salaries as a part of overhead costs, together with rising profit claims of the rentiers, i.e. rising interest and dividend payments of the corporate sector, have in sum been associated with a falling labour income share. Since management salaries are part of compensation of employees in the national accounts and thus of the labour income share, the wage share excluding (top) management salaries has fallen even more pronounced than the wage share taken from the national accounts.

Third, financialisation and neo-liberalism have weakened trade union bargaining power through several channels: increasing shareholder value and short-term profitability orientation of management, sectoral shifts away from the public sector and the non-financial business sector with stronger trade unions in many countries to the financial sector with weaker unions, abandonment of government demand management and full employment policies, deregulation of the labour market, and liberalisation and globalisation of international trade and finance.

These channels should not only have triggered falling labour income shares, but should also have been conducive to the observed increases in inequality of personal/household incomes. The major reason for this is the (even more) unequal distribution of wealth, generating capital income, which then feeds back on the household distribution of income when it comes to re-distribution between labour and capital incomes.

The Effect of Financialisation on Functional Income Distribution: Evidence for Germany

Checking the relevance of these channels for the German case, with respect to the first channel we find that neither the profit share of the financial corporate sector was higher than the profit share in the non-financial corporate sector in the period of the increasing dominance of finance starting in the early/mid 1990s (Fig. 3), nor was there a shift of the sectoral shares in gross value added towards the financial sector (Fig. 4). However, the share of the government sector in value added has seen a tendency to decline, from close to 12 % in the mid-1990s to below 10 % in 2007. Ceteris paribus, this means a fall in the aggregate wage share and a rise in the aggregate profit share, because the government sector is a non-profit sector in the national accounts. Downsizing the share of the government sector in Germany was a consequence of restrictive macroeconomic policies, and most importantly restrictive fiscal policies, focussing on price stability, improving external price competitiveness and balanced budgets in the run-up to the introduction of the euro in 1999, and then in particular during the stagnation period of the early and mid 2000s, as analysed extensively by Bibow (2003, 2005), Herr and Kazandziska (2011) and Hein and Truger (2005, 2007, 2009), for example. Apart from this sector composition effect, restrictive macroeconomic policies had another important effect on the wage and labour income shares via the depressing impact on the bargaining power of workers and trade unions, as we will argue below.

Sector gross operating surplus in Germany, 1991–2011 (per cent of sector gross value added). Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2012), our calculations and presentation

Sector shares in nominal gross value added in Germany, 1991–2011 (per cent of total). Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2012), our calculations and presentation

Regarding the second channel, the increase in top management salaries and higher profit claims of financial wealth holders, we have several indicators supporting the validity of this channel for Germany. Dünhaupt (2011) has corrected the wage share from the national accounts for the labour income of the top 1 % by assuming that the latter represent top management salaries, following the examples by Buchele and Christiansen (2007) and Glyn (2009) for the US and Atkinson (2009) for the UK.Footnote 6 The resulting wage share for direct labour shows an even steeper downward trend than the wage share from the national accounts: the difference between the two wage shares increased from 4 % points in 1992 to 5 % points in 2003 (Fig. 5). An increase in the share of top management salaries is thus associated with a decline of the share of wages for direct labour in national income.

Wage share adjusted for the labour income of top 1 % in Germany, 1992–2003 (per cent of net national income). Source: (Dünhaupt (2011), p. 27)

Extending another analysis provided by Dünhaupt (2012), we also find that, in the long-run perspective, there is substantial evidence that the increase in the profit claims of rentiers came at the expense of the workers’ share in national income (Fig. 6). In the 1980s, the fall in the wage share (compensation of employees as a share of national income, as retrieved from the national accounts) was accompanied by an increase of both the share of rentiers income (net property income consisting of interest, dividends and rents) and the share of retained earnings of corporations. However, from the 1990s, after German re-unification, until the Great Recession, the fall in the wage share benefitted mainly the rentiers’ income share. Only during the short upswing before the Great Recession did the share of retained earnings also increase at the expense of the wage share. Decomposing the rentiers’ income share (Fig. 7), it becomes clear that the increase was almost exclusively driven by a rise in the share of dividends, starting in the mid-1990s, when we observe an increasing dominance of finance and shareholders in the German economy.

Income shares in national income in Germany, 1980–2013 (%). West Germany until 1990. Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2014), our presentation based on data provided by Petra Dünhaupt

Components of rentiers’ income as a share in net national income in Germany, 1980–2013 (%). West Germany until 1990. Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2014), our presentation based on data provided by Petra Dünhaupt

In an econometric study for Germany (1960–2007), Hein and Schoder (2011) find a highly significant and strong effect of the net interest payments-capital stock ratio of the non-financial business sector on the profit share, thus confirming the notion of an interest payments-elastic mark-up affecting the distribution between capital and labour. This means that rising interest rates and costs in the 1980s contributed to the observed fall in the wage share. In the 1990s, however, the decrease in the share of net interest income in net national income would have allowed for a rise in the wage share, which, however, was prevented by the even more pronounced rise in the share of dividends in net national income, suggesting a dividend-elastic mark-up in firms’ pricing, too.

Regarding the third channel, the weakening of trade union bargaining power, we find that several indicators apply to the development in Germany from the mid-1990s until the Great Recession. First, starting in the early/mid 1990s, downsizing the government sector, as shown above, and the switch towards restrictive macroeconomic policies focussing exclusively on achieving low inflation, high international price competitiveness and (close to) balanced public budgets meant low growth and rising unemployment, in particular in the stagnation period of the early 2000s. Bibow (2003, 2005), Herr and Kazandziska (2011) and Hein and Truger (2005, 2007, 2009) have presented extensive analyses of the restrictive macroeconomic policies which have dominated the German economy since the mid 1990s, and during the trade cycle of the early 2000s until the Great Recession in particular.

Second, policies of deregulation and liberalization of the labour market (Hartz-laws, Agenda 2010) explicitly and successfully aimed at weakening trade union bargaining power through lowering unemployment benefits (replacement ratio and duration), establishing a large low-paid sector, as well as reducing trade union membership, collective wage bargaining coverage and coordination of wage bargaining across sectors and regions (Hein and Truger 2005, 2007). Table 5 summarises some supportive data on these developments. As a result of the reforms, unemployment benefits were drastically reduced, so that net- as well as gross-replacement rates declined considerably in the 2000s, even when other transfers like social assistance and housing benefits are included. While indicators for employment protection show a slight increase in employment protection for regular contracts since 2000, temporary contracts have been heavily deregulated, contributing to the emergence of a dual labour market in Germany. The weakening of trade unions in the 2000s can be seen by the decline in membership, but particular by the decline in bargaining coverage, which went down from 74 % in the late 1990s to only 61 % in 2011. While the indicators still show high degrees of coordination of wage bargaining, a trend towards decentralisation of collective bargaining can be observed. Krämer (2008) notes that bargaining coverage of branch level agreements have declined. At the same time so called opening clauses were used more extensively, which allow firms to diverge from collectively agreed standards under certain circumstances.

Third, trade and financial openness of the German economy increased significantly and put pressure on trade unions through international competition in the goods and services markets and through the threat effect of delocalisation. The foreign trade ratio (exports plus imports as a share of GDP) as an indicator for trade openness, increased from 39.1 % in the mid-1990s to 71.4 % in 2007, just before the Great Recession (Statistisches Bundesamt 2011). The foreign assets/liabilities-GDP ratios, as indicators for financial openness, increased from 56 %/40 % in 1991 to 200 %/174 % in 2007 (Deutsche Bundesbank 2014).

Fourth, shareholder value orientation and short-termism of management increased significantly, thus increasing the pressure on workers and trade unions. According to the empirical analysis by Detzer (2014) some institutional changes were important in this respect. Ownership of non-financial corporations changed considerably. The share of stock directly held by private investors halved between 1991 and 2007, while the share held by institutional investors increased significantly. Similarly, strategic investors reduced their ownership share and investors who are more likely to have purely financial interests increased it. Also fewer strategic block holders, which can shield managers from market pressure, have been present in firms. Additionally, activist hedge funds and private equity firms, which directly pressure management to favour shareholder value, have become more active in Germany. Furthermore, the development of a market for corporate control put pressure on managers to pursue shareholder value friendly strategies in order to protect themselves against hostile takeovers. For Germany, data on mergers and acquisitions and hostile takeover attempts show that the activity in this market increased considerably in the 1990s and early 2000s. Important factors facilitating this were legal changes in the 1990s and early 2000s, which gradually removed obstacles to takeovers, and the gradual dissolution of the German company network. In particular the big banks actively reduced their central role in the network since the 1990s due to their increased preference for investment banking activities.

Empirical analyses of the effects of financialisation on investment in capital stock of non-financial corporations have taken the financial profits of non-financial corporations as an indicator for the ‘preference channel’ of financialisation and increasing shareholder value orientation of managements. Rising financial profits indicate an increased preference of management of non-financial business for short-term profits obtained from financial investment, as compared to profits from real investment, which might only be obtained in the medium to long run. As Fig. 8 shows, this is exactly what can be found for German non-financial corporations starting in the late 1990s/early 2000s. Property income, consisting of interest, distributed income of corporations (i.e. dividends, property income attributed to insurance policy holder and rents) and reinvested profits from FDI, increased significantly as a share of gross operating surplus. This increase was driven considerably by an increase in interest payments received in a period of low interest rates and by an increase in dividend payments obtained. The increase in the relevance of both types of financial profits indicates an increasing relevance of financial investment, as compared to investment in real capital stock of non-financial business. Another indicator for the effects of an increasing shareholder value orientation of management on investment in capital stock is the share of profits distributed to shareholders. Figure 9 shows that such a phenomenon can be observed for German non-financial corporations, too. The share of distributed property income in the gross operating surplus of non-financial corporations tended to rise starting in the mid-1990s. This increase was driven almost exclusively by an increase in the share of distributed income of corporations, i.e. dividends, whereas the share of interest payments in the gross operating surplus stagnated or even declined.

Sources of operating surplus of non-financial corporations, Germany, 1991–2011 (per cent of sector gross operating surplus). Total property income includes additionally property income attributed to insurance policy and rents. Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2012), our calculations

Uses of operating surplus of non-financial corporations, Germany, 1991–2011 (per cent of sector gross operating surplus). Total property income includes additionally rents. Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2012), our calculations

Conclusions

In this paper we have provided a deeper investigation of the long-run effects of financialisation on income distribution before the recent financial and economic crises for Germany, one of the major mercantilist export-led countries. The analysis built on a Kaleckian approach towards the examination of the effects of financialisation on income shares, as suggested by Hein (2014a). First, we have shown that Germany has seen considerable re-distribution of income since the early 1980s, which accelerated in the early 2000s: a tendency of the labour income share to decline; rising inequality in the personal and household distribution of market and disposable income (although government redistribution has not been weakened), in particular at the expense of very low incomes; and a rise in top income shares, considering the top-10 % income share. Examining the three main channels through which financialisation (and neo-liberalism) are supposed to have affected the wage or the labour income share, according to the Kaleckian approach, we have provided evidence for the existence of each of these channels in Germany since the mid 1990s, when several institutional changes provided the conditions for an increasing dominance of finance. First, the shift in the sectoral composition of the economy away from the public sector and towards the corporate sector, without favouring the financial corporate sector, however, contributed to the fall in the wage and the labour income share for the economy as a whole. Second, the increase in management salaries as a part of overhead costs together with rising profit claims of the rentiers, in particular rising dividend payments of the non-financial corporate sector, have in sum been associated with a falling wage and labour income share, although management salaries are a part of employee compensation, and thus also form part of the wage share, in the national accounts. The latter implies that the share of direct labour, excluding top management salaries, has fallen even more drastically. Third, financialisation and neo-liberalism have weakened bargaining power of German trade unions through several channels: downsizing the role of the public sector and of government demand management, active policies of deregulation and liberalization of the labour market explicitly and successfully aimed at weakening workers and trade unions, increasing trade and financial openness of the German economy and, finally and in particular, rising shareholder value and short-term profitability orientation of management. Any policies aiming at raising the labour income share and improving income distribution in Germany, as part of a wage- or mass income-led growth strategy, avoiding the problems of the unsustainable export-led mercantilist and debt-led consumption boom regimes before the crisis, would have to tackle these three channels.Footnote 7

Notes

See for example, Berg and Ostry (2011), Berg et al. (2008), Fitoussi and Stiglitz (2009), Horn et al. (2009), Kumhof et al. (2012), Kumhof and Ranciere (2010), Michell (2015), Rajan (2010), Stiglitz (2012), Stockhammer (2010a, b, 2012a, b), UNCTAD (2009); Van Treeck (2014), Van Treeck and Sturn (2012, 2013) and Wade (2009).

On the development of financialisation in a broader set of countries, see also the other more recent country studies published in the FESSUD Studies in Financial Systems (http://www.fessud.eu).

Recently, also the (OECD (2012b), Chapter 3) has presented such corrected wage shares for Canada, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and the US.

References

Alvaredo F, Atkinson AB, Piketty T, Saez E (2014) The world top incomes database. http://g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/topincomes/

Anselmann C, Krämer H (2012) Completing the bathtub? The development of top incomes in Germany, 1907–2007. SOEP papers on multidisciplinary panel data research, No. 451, DIW Berlin

Atkinson AB (2009) Factor shares: the principal problem of political economy? Oxf Rev Econ Policy 25(1):3–16

Bach S, Corneo G, Steiner V (2009) From bottom to top: the entire distribution of market income in Germany, 1992–2003. Rev Income Wealth 55:303–330

Berg AG, Ostry JD (2011) Inequality and unsustainable growth: two sides of the same coin? IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/11/08. IMF, Washington, DC

Berg AG, Ostry JD, Zettelmeyer J (2008) What makes growth sustained? IMF Working Paper 08/59. IMF, Washington, DC

Bibow J (2003) On the ‘burden’ of German unification. Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Q Rev 56:127–169

Bibow J (2005) Germany in crisis: the unification challenge, macroeconomic policy shocks and traditions, and EMU. Int Rev Appl Econ 19:29–50

Buchele R, Christiansen J (2007) Globalization and the declining share of labor income in the United States. Paper prepared for the 28th international working party on labor market segmentation, Aix-en-Provence, France, 5–7 July 2007. http://gesd.free.fr/paper419.pdf

Detzer D (2014) Inequality and the financial system—the case of Germany. Global Labour University Working Paper, No. 23. The Global Labour University (GLU)

Detzer D, Dodig N, Evans T, Hein E, Herr H (2013) The German financial system. FESSUD Studies in Financial Systems, No. 3, University of Leeds

Detzer D, Hein E (2014) Finance-dominated capitalism in Germany—deep recession and quick recovery. Working Paper, No. 39/2014. Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin School of Economics and Law, and FESSUD Working Paper, No. 54, University of Leeds

Deutsche Bundesbank (2014) Time series database. http://www.bundesbank.de/Navigation/EN/Statistics/Time_series_databases/Macro_economic_time_series/macro_economic_time_series_node.html

Dünhaupt P (2011) The impact of financialization on income distribution in the USA and Germany: a proposal for a new adjusted wage share. IMK Working Paper 7/2011, Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at Hans Boeckler Foundation, Düsseldorf

Dünhaupt P (2012) Financialization and the rentier income share—evidence from the USA and Germany. Int Rev Appl Econ 26:465–487

Dünhaupt P (2013) The effect of financialization on labor’s share of income. Working Paper, No. 17/2013, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin School of Economics and Law

Epstein GA (2005a) Introduction: financialization and the world economy. In: Epstein GA (ed) Financialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Epstein GA (ed) (2005b) Financialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

European Commission (2010) AMECO database, spring 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/db_indicators/ameco/index_en.htm

Fitoussi JP, Stiglitz J (2009) The ways out of the crisis and the building of a more cohesive world. OFCE Document de Travail, No. 2009-17, Paris

Glyn A (2009) Functional distribution and inequality. In: Salverda W, Nolan B, Smeeding TM (eds) The Oxford handbook of economy inequality. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Grabka MM, Goebel J (2014) Reduction in income inequality faltering. DIW Econ Bull 1(2014):16–25

Hein E (2011) Redistribution, global imbalances and the financial and economic crisis—the case for a Keynesian New Deal. Int J Labour Res 3:51–73

Hein E (2012) The macroeconomics of finance-dominated capitalism—and its crisis. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Hein E (2014a) Finance-dominated capitalism and re-distribution of income—a Kaleckian perspective. Camb J Econ (forthcoming, advance access). doi:10.1093/cje/bet038

Hein E (2014b) Distribution and growth after Keynes: a post-Keynesian guide. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Hein E, Mundt M (2012) Financialisation and the requirements and potentials for wage-led recovery—a review focussing on the G20. Conditions of Work and Employment Series, No. 37, International Labour Organization (ILO)

Hein E, Mundt M (2013) Financialization, the financial and economic crisis, and the requirements and potentials for wage-led recovery. In: Lavoie M, Stockhammer E (eds) Wage-led growth: an equitable strategy for economic recovery. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Hein E, Schoder C (2011) Interest rates, distribution and capital accumulation—a post-Kaleckian perspective on the US and Germany. Int Rev Appl Econ 25:693–723

Hein E, Truger A (2005) What ever happened to Germany? Is the decline of the former European key currency country caused by structural sclerosis or by macroeconomic mismanagement?. Int Rev Appl Econ 19:3–28

Hein E, Truger A (2007) Germany‘s post-2000 stagnation in the European context—a lesson in macroeconomic mismanagement. In: Arestis P, Hein E, Le Heron E (eds) Aspects of modern monetary and macroeconomic policies. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Hein E, Truger A (2009) How to fight (or not to fight) a slowdown. Chall Mag Econ Aff 52(2):52–75

Herr H, Kazandziska M (2011) Macroeconomic policy regimes in western industrial countries. Routledge, Abingdon

Horn G, Dröge K, Sturn S, van Treeck T, Zwiener R (2009) From the financial crisis to the world economic crisis. the role of inequalitiy. IMK Policy Brief. Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at Hans-Boeckler Foundation, Düsseldorf

Kalecki M (1954) Theory of economic dynamics. George Allen and Unwin, London

Krämer B (2008) Germany: industrial relations profile. Institute of Economic and Social Research (WSI). http://www.bollettinoadapt.it/old/files/document/6494EIRO_GERMANY_201.pdf

Krippner GR (2005) The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Econ Rev 3:173–208

Kristal T (2010) Good times, bad times. Postwar labor’s share of national income in capitalist democracies. Am Sociol Rev 75:729–763

Kumhof M, Lebarz C, Ranciere R, Richter AW, Throckmorton NA (2012) Income inequality and current account imbalances. IMF Working Papers 12/08, Washington, DC

Kumhof M, Ranciere R (2010) Inequality, leverage and crises. IMF Working Papers 10/268, Washington, DC

Michell J (2015) Income distribution and the financial and economic crisis. In: Hein E, Detzer D, Dodig N (eds) The demise of finance-dominated capitalism: explaining the financial and economic crises. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (forthcoming)

OECD (2008) Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. OECD, Paris

OECD (2012a) OECD.StatExtracts. http://stats.oecd.org

OECD (2012b) Employment outlook. OECD, Paris

OECD (2014) OECD.StatExtracts. http://stats.oecd.org

Orhangazi Ö (2008a) Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector: a theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973–2003. Camb J Econ 32:863–886

Orhangazi Ö (2008b) Financialization and the US economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Palley TI (2008) Financialisation: what it is and why it matters. In: Hein E, Niechoj T, Spahn P, Truger A (eds) Finance-led capitalism? Macroeconomic effects of changes in the financial sector. Metropolis, Marburg

Palley TI (2013) Financialization: the economics of finance capital domination. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Palma JC (2009) The revenge of the market on the rentiers. Why neo-liberal reports of the end of history turned out to be premature. Camb J Econ 33:829–869

Rajan RG (2010) Fault lines: how hidden fractures still threaten the world economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Statistisches Bundesamt (2011) Export, import, Globalisierung. Deutscher Außenhandel, Statistisches Bundesamt, August, Wiesbaden. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Aussenhandel/Gesamtentwicklung/AussenhandelWelthandel5510006127004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

Statistisches Bundesamt (2012) Sector accounts—annual results—1991 to 2011. Statistisches Bundesamt, August, Wiesbaden. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/VolkswirtschaftlicheGesamtrechnungen/Nationaleinkommen/SectorAccountsAnnualresultsPDF_5812106.pdf

Statistisches Bundesamt (2014) Genesis-online data base. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online

Stiglitz J (2012) The price of inequality. How today’s divided society endangers our future. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Stockhammer E (2008) Some stylized facts on the finance-dominated accumulation regime. Compet Change 12:189–207

Stockhammer E (2009) Determinants of functional income distribution in OECD countries. IMK Studies 5/2009. Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at Hans Boeckler Foundation, Duesseldorf

Stockhammer E (2010a) Income distribution, the finance-dominated accumulation regime, and the present crisis. In: Dullien S, Hein E, Truger A, van Treeck T (eds) The world economy in crisis—the return of Keynesianism? Metropolis, Marburg

Stockhammer E (2010b) Neoliberalism, income distribution and the causes of the crisis. Research on money and finance. Discussion Paper No. 19, Department of Economics, SOAS, London

Stockhammer E (2012a) Financialization, income distribution and the crisis. Investig Econ 71(279):39–70

Stockhammer E (2012b) Rising inequality as a root cause of the present crisis. Working Paper Series No. 282, Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), Universtiy of Massachussets, Amherst

Stockhammer E (2013a) Why have wage shares fallen? An analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution. In: Lavoie M, Stockhammer E (eds) Wage-led growth: an equitable strategy for economic recovery. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Stockhammer E (2013b) Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution. Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 35. ILO, Geneva

SVR (2011) Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung Jahresgutachten 2011/12. Statistisches Bundesamt, Verantwortung für Europa wahrnehmen, Wiesbaden

Tomaskovic-Devey D, Lin KH (2013) Financialization and US income inequality, 1970–2008. Am J Sociol 118:1284–1329

UNCTAD (2009) The global economic crisis. Systemic failures and multilateral remedies. UNCTAD, New York

Van Treeck T (2009) The political economy debate on ‘financialisation’—a macroeconomic perspective. Rev Int Polit Econ 16:907–944

Van Treeck T (2014) Did inequality cause the US financial crisis? J Econ Surv 28:421–448

Van Treeck T, Hein E, Dünhaupt P (2007) Finanzsystem und wirtschaftliche Entwicklung: neuere Tendenzen in den USA und in Deutschland. IMK Studies 5/2007, Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at Hans Boeckler Foundation, Düsseldorf

Van Treeck T, Sturn S (2012) Income inequality as a cause of the Great Recession? A survey of current debates. Conditions of Work and Employment Series, No. 39, International Labour Organization (ILO), Geneva

Van Treeck T, Sturn S (2013) The role of income inequality as a cause of the Great Recession and global imbalances. In: Lavoie M, Stockhammer E (eds) Wage-led growth: an equitable strategy for economic recovery. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Visser J (2013) ICTWSS: database on institutional characteristics of trade unions, wage setting, state intervention and social pacts in 34 countries between 1960 and 2012, version 4. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies, University of Amsterdam. http://www.uva-aias.net/208

Wade R (2009) From global imbalances to global reorganisations. Camb J Econ 33:539–562

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the results of the project Financialisation, Economy, Society and Sustainable Development (FESSUD). It has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under Grant Agreement No. 266800. We are grateful to Petra Dünhaupt for helping us with the data for Figs. 2, 5, 6 and 7 and to Jeffrey Althouse for editing the English style. We have also benefitted from comments by Dirk Ehnts, Achim Truger, Alberto Zazzaro and an anonymous referee. Remaining errors are, of course, ours. Website: http://www.fessud.eu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hein, E., Detzer, D. Finance-Dominated Capitalism and Income Distribution: A Kaleckian Perspective on the Case of Germany. Ital Econ J 1, 171–191 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-014-0001-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-014-0001-4